- Home

- Zac Gorman

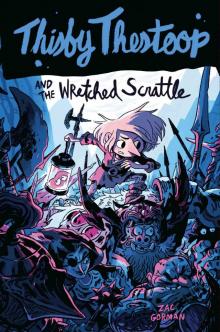

Thisby Thestoop and the Wretched Scrattle Page 2

Thisby Thestoop and the Wretched Scrattle Read online

Page 2

Thisby smiled, revealing a chipped tooth she’d recently acquired during a run-in with an impatient rock golem.

“Oh, yeah?”

Thisby grabbed the sides of the boat and shook it back and forth violently.

“STOP IT! STOP IT! NOT FUNNY!” Mingus screamed, though his laughter undermined his protest.

Thisby stopped, held up her hands in a gesture of mock defeat, and sat back down. She wasn’t about to admit it, but she’d actually made herself sick as well. They’d been traveling the river all day, tending to the aquatic residents of the Black Mountain, and spending that much time on the water had begun to take its toll.

There was only one river in the Black Mountain, and it wound its way through every floor of the dungeon, flowing both upward and downward without beginning or end, sprouting off into tiny streams, which fed into larger bodies of water that quite often seemed far too vast for the amount of water being supplied to them. Any attempt to comprehend the physics of the river would drive a sane person mad, as it had done with Cornish Planesse, one of the original thirty-three architects who’d constructed the dungeon. Right up until the day he died, Cornish could not so much as even see a glass of water without becoming irrationally angry.

Common sense and gravity would suggest that the river should have flowed down the mountain from top to bottom, and it did, for about half of it. The confusing part was that somehow, the other half of the river flowed back up the mountain until it met with the point where it began, creating a seamless ribbon that flowed counterclockwise around the entire dungeon. More confusing still was that the wizards who examined the river—including the great Elphond the Evil, first Master of the Black Mountain himself—found no indication of magical tampering. The only clue as to something unusual about the river’s design was a series of copper pipes discovered beneath the bed of the river in some areas. These were presumably an artifact left over from the Dünkeldwarves, who’d begun construction in the Black Mountain centuries before Elphond the Evil and his team of architects had arrived to finish the job, but the pipes’ function had yet to be properly explained, so the mystery of the Floating River—as it had come to be called—persisted.

Due to the river’s improbable nature, if Thisby traveled downstream, she could make her way around the entire dungeon from top to bottom in less than two days’ time, barely ever having to touch her paddle to the water. It was nice. The Floating River pretty much carried her where she needed to go, and although it was far slower than using her shortcuts on foot, it was also much easier on her legs. It was almost a perfect mode of travel. Almost. Because this was the dungeon, there were, of course, several other complications.

The first of these were the narrow passages. Many of them were so small that Thisby had to cram her backpack way down into the base of the rowboat and hunch over until her back ached, just to squeeze through. These tunnels made moving anything larger than a boat with a single, small passenger a pipe dream. Second, even though the river was basically one long ribbon, that did not mean it was simple to navigate. The river branched off into thousands of fingers both large and small, and if you weren’t careful, it was all too easy to get stuck in a dead end—and worse yet, once you were stuck, any attempt to paddle upstream against the strong current was next to impossible. This meant that wherever you ended up, you were more or less stranded. And then there was the third point. The areas surrounding the river—as well as the river itself—were breeding grounds for some of the biggest, wildest, all-around-nastiest monsters in the entire dungeon.

Unsuspecting adventurers who thought they’d found a clever shortcut through the dungeon by navigating the river would all too often be gobbled up by giant albino alligators who lurked just below the surface of the water or dragged under by a horde of angry merpeople. There were countless dangers hidden beneath the black, glassy surface of the Floating River, and if you took a wrong turn, it’d very likely be your last. Even Thisby, with her unsurpassed knowledge of the dungeon, didn’t dare travel the river without her supply of meticulously updated, hand-drawn maps. It was for this myriad of reasons that it was typically safer—not to mention faster, if you knew the proper shortcuts, which of course she did—to walk. Which was exactly what she did all but one day of every month, when it was time to tend to the dungeon’s aquatic residents.

Thisby and Mingus had already passed the turn at the lowest point of the river when her pocket began to glow. From it, she withdrew what resembled an ornate golden pocket watch with a small, flashing white crystal on the front and flipped it open. Inside, as clear as day, was the Master of the Black Mountain sitting in his study.

“Keeper,” he said. The Master never called her by name. Frankly, she wasn’t even certain he remembered it—not even after she’d saved the dungeon. “Finish up with your work and meet me in the castle. We have some important business to discuss.”

Thisby’s mouth opened and shut as she tried to find a response but failed on her first, second, and then third attempt. His request had caught her off guard. Even though the Master had become increasingly reliant on Thisby as of late, communicating with her through her “scrobble”—the nickname Thisby had given the magical device through which she now spoke—she hadn’t spoken to him in person since shortly after the Battle of Darkwell, when the entire dungeon had nearly been overrun by Deep Dwellers. She tried not to sound as worried as she felt by the unprecedented suggestion that they meet face-to-face.

“Uh, yes. Definitely. I just need to take care of a few more things. I should be back in a few hours if I hurry?”

“Do,” he said.

There was a long pause during which Thisby got it into her head that she was definitely, absolutely supposed to say something. She wrinkled her nose and opened her mouth as if to speak, assuming that maybe the issue was merely that her lips were in the way of her words. She did this a few more times until a few of them finally managed to dribble out.

“I hear the shovelball finals are starting soon. Do you think the Bisby Bigbacks have what it takes? Grunda tells me that sometimes you watch the games from the blackdoor room. So I just, uh . . . well . . . I wondered . . .”

The Master blinked at her a few times.

“Just hurry,” he added before the screen of her scrobble went black.

Thisby looked up just in time to dodge a passing stalactite as the boat continued along down the river, carried forward by the endless current.

“What do you think he wants?” she asked.

“Maybe you’re finally getting that promotion.”

This was Mingus’s idea of a joke. Since the Battle of Darkwell a year ago, things in the dungeon had changed quite a bit, and Thisby found herself in an unusual position. Essentially, she was running the dungeon, and things had never been better.

After the battle, the Master seemed to believe that he’d earned an early retirement, and in short order he’d begun to relegate all his duties to the remaining members of his staff; namely Thisby, who served as gamekeeper, and Grunda the goblin, who was promoted to liaison to Castle Grimstone following the untimely death of the Master’s previous liaison, the traitorous Roquat. As it turned out, Thisby and Grunda did a much better job than anybody had previously thought possible.

Under their watch, the dungeon had been running like Dünkeldwarven automata. Everything was cleaner and better organized than it had ever been. The resident monsters were well fed and content, and there’d even been several successful construction projects that restored access to previously unreachable areas of the dungeon, such as the blood bee apiary and the harpy roost. There was even talk about beginning reconstruction on the areas of the City of Night that had been devastated during last year’s tarasque rampage. Unfortunately for Thisby, all this extra work came without a promotion (or pay of any kind, it should be noted) and as it was, she’d been having a hard time understanding exactly what the Master was “Mastering” these days.

She rolled her eyes at Mingus.

> “I’m not holding my breath.”

As much as she hated to admit it, there was a small part of her heart that leapt when Mingus had suggested the idea. After all, why shouldn’t she get a promotion? She deserved it. After saving everyone from Ingo and the Deep Dwellers and then spending the rest of the year making the dungeon better than she’d ever seen it in her time as gamekeeper, why shouldn’t she be promoted? Maybe the Master was ready to step aside and name her the new Master of the Black Mountain.

She shook the thought from her head, but it was too late. Even the passing thought had been enough to make her intestines twist up into a knot that would take some time to untie. It wasn’t that she didn’t feel capable of being the Master; there was just something that felt wrong about the whole idea. Last year after the invasion, several of the monsters had begun to refer to her as mara’wak kombeh, a sort of honorary title meaning “Master of the Black Mountain” that was borrowed from the kobolds—and it’d made her uncomfortable in a way that she hadn’t expected. Fortunately, she knew there was no reason to get worked up like she had. Nobody simply relinquished the position of Master of the Black Mountain. It just wasn’t done. The Master was a position you only left the hard way, traditionally with a knife sticking out of your back.

No. For now, at least, Thisby was happy as gamekeeper. After all, she was still just a few weeks from turning thirteen. There’d be plenty of time to worry about this “promotion” stuff when she was older. For now, all she really wanted was a little help. Maybe she’d bring that up in their meeting.

The boat bounced down the river, and Thisby hurriedly plunged her paddle into the inky water, turning the vessel down the leftmost tunnel. It was hard to tell that they’d rounded the bend near the bottom of the river and had begun their ascension—the angle was subtle here and the tunnel very narrow—but Thisby swore for a second she felt her ears pop as their altitude changed.

When the rowboat emerged from the tunnel, Thisby had Mingus kill his light and leaned forward so that she was almost lying flat on her stomach in the boat, hidden beneath its edge. The boat slid silently out into the open chamber as she lay still, enveloped by darkness, feeling only her heartbeat and the gentle rocking of her boat. In the overwhelming silence of the cavern, she was painfully aware of the sound of her own breathing and fought to get it under control. Once she’d done so, Thisby pressed up into a push-up position, peering over the lip of the boat out into the nothingness that surrounded her.

The rowboat drifted slowly on through the darkness. Without any point of reference, it soon became difficult to tell if they were even moving at all. The feeling was unnerving.

A story sprang to mind. It was one that Grunda had told her before she took her first trip down the Floating River, though it’d happened long before Thisby was born. It concerned the fate of Pedrosa Porret, a famous adventurer who died in Long Lost Lake—the lake at the very bottom of the Floating River, which Thisby always avoided if she could help it, like today—after he ran out of lantern oil. He was stranded, adrift in complete darkness, unable to come to shore because his vessel was surrounded by dire crocodiles, until he ran out of food and perished. Only, when his body was eventually found by the gamekeeper, despite what he’d scrawled in his journal, there were no signs of dire crocodiles anywhere and his body was noticeably uneaten. Had he simply gone mad in the dark? It seemed entirely possible.

Thisby shivered. Why couldn’t Grunda ever tell her stories with happy endings?

There was snuffling in the dark. The sound of nostrils the size of grapefruits sucking in long breaths, followed by the gentle splashing of things slipping below the water. The rowboat rocked as if something big had passed underneath.

There was a faint light now from the pale glow of bioluminescent cave mushrooms. It was just bright enough that Thisby could see the outlines of the massive beasts on the other side of the cave, but not bright enough to make out any distinct features. The creatures had bodies like hippopotamuses but necks that stuck out like a giraffe’s, which they craned down into the water to root around for plants and algae.

Thisby recognized them as catoblepas. Big, sure enough, but they weren’t exceptionally dangerous unless they felt threatened. If that happened, though . . . look out. Thisby had once seen a catoblepas knock a wyvern clear out of the sky with one swing of its massive clubbed tail.

In the overwhelming silence of the cavern, Thisby was painfully aware of the sound of her own breathing.

The silhouette of one of the creatures lifted its massive head from the water and sniffed the air in Thisby’s direction as her boat glided silently past. She couldn’t make out the details of its face in the dark, but she could feel its presence and knew that it was watching her pass. Though it was maybe forty yards from her boat, it was a distance she knew a creature that size could cross quickly if it felt threatened. Thisby watched the outline of its warthog-like head bob up and down as it smelled her from across the water. Thisby nodded silently in the direction of the catoblepas, which snorted once before returning to its business of rooting around underwater. As she steered the boat out of the chamber, she dropped several bags of powder into the river to help facilitate algae growth, and left the catoblepas to enjoy their meal.

After they’d put enough distance between themselves and the catoblepas, Thisby sat up and Mingus began to glow again, faintly, so as not to disturb the light-sensitive creatures in the tunnels and caves along the river. Thisby smiled to herself. Partly from the relief of being able to see where she was going again, and partly from the satisfaction that after so many years, after so much work, the dungeon was finally running more smoothly than it ever had before.

Chapter 3

The dungeon was in the worst shape it had ever been in, and it was entirely everybody else’s fault.

This was the sole, miserable thought of the Master of the Black Mountain as he stared out through the window of Castle Grimstone’s highest tower—which also happened to be his office—surveying what he could of Nth. It was very little. The sky was completely overcast that day, which, being above the clouds, meant that it was nearly impossible to see through, though occasionally a strong breeze would cause them to stir and through the swirling gray soup he’d catch a fleeting glimpse of Three Fingers and the rolling hills that lay beyond. Straight on from there to the west, at least a week’s journey over the hills and through the woods, was Oryzia, the capital city, home to Lyra Castelis and the King of Nth himself.

“King of pffth!” spat the Master to himself and the walls.

When the Master was younger, he’d dreamt of being a king himself. Now he just wanted to be left alone. Unfortunately, after the Battle of Darkwell, peace and quiet had no longer been an option. Instead he had to deal with that nosy old bag of goblin warts, Grunda, and the only mildly less annoying gamekeeper. They were both gunning for his job. He knew it. Everyone knew it. At least some small part of him wished they’d just kill him already and be done with it. At least then he wouldn’t have to keep hearing endless reports about how the Floating River was getting too dirty for the merpeople, or how the mummies needed fresh bandages, or how the trolls had gotten sick from rancid meat—ridiculous!

Worst of all, however, was that for some reason, the once plentiful stock of brave young heroes willing to risk their lives for treasure or glory down in the dungeon seemed to be at an all-time low. Without adventurers, there was no dungeon. That was something the pesky little gamekeeper girl and the old goblin didn’t seem to understand. Adventurers were the lifeblood of the dungeon. Without them—

KNOCK! KNOCK! KNOCK-KNOCK-KNOCK!

The Master shuddered. It was a knock he knew all too well. For the last few weeks he’d actually woken up in cold sweats, dreaming he’d heard it.

“Come in,” he moaned.

His chamber door creaked open and a wrinkly old goblin trotted in. She was carrying a box that was soaking through the bottom and dripping something gray and oily on his black marble

floor.

“Look at this!” she squawked. “Can you believe this?”

Her voice was like hearing fingernails on a chalkboard—no, it was worse than that. Her voice was like hearing fingernails on a chalkboard, only they’re your fingernails and they’ve been ripped clean off your fingers.

Grunda dropped the box at his feet and it landed with a sickening splortch! Her thin goblin fingers pulled the flaps open before the Master had a chance to look away, and he found himself staring down at what looked—and smelled—like a box full of spoiled tapioca and ogre snot.

“The new meat supply is way too salty for the slughemoths! They’re completely melting! Look at them! It’s disgusting!”

The Master agreed but didn’t see why it was his problem. He turned away from the box and walked over to his desk, letting out a long, measured sigh as he went.

“I told you not to bother me with this stuff. If you have a problem, you take care of it.”

Grunda glared at him from across the room.

“And what exactly do you do?” she asked.

This was it, he thought. This was exactly it. This was it in a nutshell. This was what had been going wrong with the dungeon ever since the gamekeeper—Thessily? Theremin?—had “saved” everyone from the deep dwellers . . . nobody was afraid anymore. Not of him, not of one another.

It’d been hard for him to place it at first. He was aware that something had shifted in the dungeon, in the proper order of things, but it took him awhile to figure out what it was exactly. The problem was that once the monsters of the dungeon had united to stop the invasion, they’d become far too friendly with one another. The random violence and chaos of the dungeon had slowed to a crawl and was replaced by a sort of, ugh, cooperation. Everything was “nice.” Unfortunately for the Master, “nice” didn’t jibe with his management style.

For years, he’d managed to be an effective ruler while doing very little by maintaining an aura of fear throughout the Black Mountain. The creatures were afraid of one another. They were afraid of him, afraid of the Deep Dwellers, afraid of the humans lurking just outside the mountain. But it’d all begun to unravel that one infamous night. When the monsters of the dungeon came together, united toward a single cause, they realized that they didn’t have to be afraid, not of him, not of the Deep Dwellers, not of anything. It’d all blown up in his face. After the battle, he’d continued to do very little, only now he was worried that it was beginning to show. Now that nobody feared him, there was no way to maintain order.

Thisby Thestoop and the Wretched Scrattle

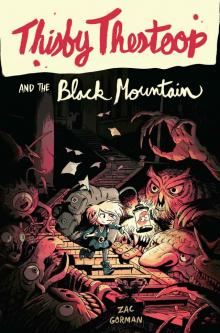

Thisby Thestoop and the Wretched Scrattle Thisby Thestoop and the Black Mountain

Thisby Thestoop and the Black Mountain