- Home

- Zac Gorman

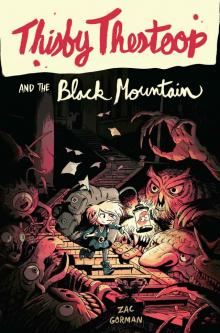

Thisby Thestoop and the Black Mountain

Thisby Thestoop and the Black Mountain Read online

Dedication

FOR SUZY

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 17.5

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 22.5

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

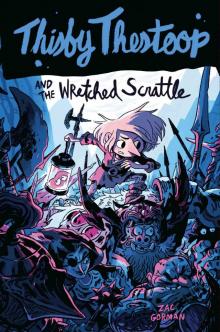

Excerpt from Thisby Thestoop and the Wretched Scrattle

About the Author and Illustrator

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

Far below, a torch flickered in the darkness. Its bright orange flame bobbed along like a buoy adrift on a blackened sea, swaying rhythmically as it went and casting strange, nervous shadows amid the ruins. The light followed an irregular path, weaving between pillars engraved with long-forgotten languages, ducking beneath barely-held-together arches, and ambling through doorways leading to yet more doorways through an endless labyrinth of rooms, until it arrived at last at a passageway, where it paused.

Attached to the end of the torch—the nonburning end, of course—was a man, clad in full plate armor, upon whose shoulders rested the fate of an entire village. He held the torch out at arm’s length and waited for something, for anything to give him a reason to turn around. But nothing came. There was no noise, no movement. Nothing but a chamber of impressive darkness. Darkness so impressive that it took on physical characteristics. It had a weight, a texture, a smell. This particular darkness smelled something like an old root cellar after a thunderstorm.

The man stood at the doorway for some time considering his options, but finally, seeing no better alternatives, stepped forward into the dark.

We call him “the man” here because his name does not matter. His name does not matter because this man did not succeed in his quest, and therefore his name did not need to be remembered for songs or epic poems or history books. No parents proudly named their children after this man. No sculptors needed to know how his name was spelled when they were engraving their statues of him.

No, this man died. Just like all the adventurers who came before him to this horrid place seeking treasure, whether for their own selfish gains or for noble reasons such as saving their village from a terrible plague by returning with a vial of magic elixir. The reason didn’t matter. It never did. Neither did it matter that this man was handsome, or brave, or skilled with a sword. There are certain traps that cannot be escaped once entered.

The man heard a noise behind him and spun around, but only darkness stared back. If he was a coward, he’d have run. It wouldn’t have helped.

He held up his torch and turned to watch the shadow play on the wall. His own puppet, the shadow he cast, was as high as the rough-hewn cavern, stretched out like a grotesque giant. For a moment, he thought he saw something move behind it. Another shadow, perhaps, just beyond the periphery of his vision. He heard the noise again, closer now. He drew his sword. The familiar shhiiiiiiiinng! of his steel blade against its hilt rang out like a challenge to the darkness. This far below in the dungeon, however, the darkness always won.

With a gust of cold air that sounded a bit like a cruel laugh, his torch was extinguished. The darkness washed over him, as thick as mud, and the only solace he was offered was that he never saw the creature bearing down on him.

Chapter 1

Thisby Thestoop wiggled her toes in her boots, carefully placing her pinky toe over the toe-which-comes-next-to-the-pinky-toe. It had become a bit of a nervous habit, you might say; but if Thisby was nervous, you’d never have known it from her businesslike demeanor or the tuneless song she hummed mindlessly as she went. This was especially interesting considering that Thisby was currently inching along a damp rock wall in complete darkness, an arm’s length away from a sleeping troll.

It probably goes without saying, but most people do not hum around sleeping trolls. Thisby, however, knew that trolls were notoriously hard to wake with noise but alarmingly easy to rouse with smells, particularly the scent of meat. Which was why in all of the many, many pockets in the overlarge backpack she always wore, each serving of meat—and there were many—was dutifully wrapped in heavy butcher’s paper, and several bundles of sweetgrass were tied to the outside of her pack to mask the smell. Thisby knew to do this because it was her job to know these things, and she was quite good at her job.

Thisby was quite good at most things, as a matter of fact, but not for the reasons most people might assume. She wasn’t born particularly clever or brave. She couldn’t move like a shadow or shoot an arrow through the eye of a needle. And she most definitely wasn’t predestined to greatness through some divine prophecy or “Chosen One” hooey. No, Thisby Thestoop was astoundingly average in every way, save one—a trick she’d learned when she was quite young and had made into a habit through sheer force of will, first as a means of survival and later as a way to slake her endless curiosity: Thisby took diligent notes.

The troll mumbled something in its sleep. Its voice sounded like a bunch of rocks rolling around inside a cast-iron pot. Thisby crouched low to let the bottom of her backpack touch the cold cave floor before squeezing together her shoulder blades and wriggling free. The bag stood upright on its own as she got onto her tippy toes to dig around inside the main compartment.

A quiet voice whispered in her ear, “He wants to crunch on your bones.”

Thisby continued digging.

“It’s what he said. In Trollish,” the voice continued.

“You don’t have to whisper, Mingus,” said Thisby.

She unhooked her lantern and whirled it around the backpack gracefully, illuminating the fastidiously buttoned pouches, which she promptly set about opening. As the little jelly inside the lantern slid to and fro in his smooth glass enclosure, his glow changed from a warm, golden yellow to a sickly chartreuse.

“BE CAREFUL! YOU MIGHT CRACK MY JAR!” shrieked Mingus.

Thisby ignored him.

She dunked the lantern inside the bag’s main compartment. It was followed shortly thereafter by her entire head, well past her shoulders. The inside of the backpack was exactly as organized as Thisby’s notes—which is to say, not very well—although that, perhaps, depended upon who was looking. Thisby always seemed to know exactly where to find what she was searching for in the maze of boxes, bags, jars, and oddly shaped containers. Despite being crammed full of goods, the backpack was still large enough for Thisby to crawl inside and take a nap—not that she usually had time for naps, but if, on a rare slow workday down in the dungeon, you came across a large, snoring backpack, well then, mystery solved.

“Brighter, please,” said Thisby.

“It’s rather cold in here today. I wish I had a sweater. But I suppose I’d need arms to wear a sweater. Perhaps a scarf? But I suppose that would require a neck,” said Mingus. The jelly glowed ever more brightly as he spoke, illuminating the inside of the bag with a pleasant ochre hue. He watched Thisby as she worked. At least, it appeared that way.

Back when they first met, Thisb

y had been kind enough to make him a pair of makeshift eyes out of painted buttons, so she knew where to look when they spoke. She’d taught him how to bend a crease to use for a sort of pretend mouth as well. He’d wiggle it open and closed when he was talking, despite the fact that the sound he produced actually just kind of vibrated out of his whole body. He’d even learned how to make some basic facial expressions by reshaping the jelly around his faux eyes to look nervous or surprised.

“Ouch!” Thisby exclaimed, sucking at her finger.

Mingus did his best disgusted face. “When’s the last time you washed that finger?”

“It’s fine!” she said, missing the point. “It’s just a little pinprick. What do you want me to do? Let it bleed everywhere?”

“No, I—”

“Wait! Maybe you could use your mysterious slime healing magic to fix it!” she teased, waving her bloody finger toward his jar.

“Stop it! Cut it out!” he squealed.

It was an inside joke.

Once, on one of the rare occasions when Thisby had been forced to physically lift Mingus out of his jar—rare indeed because Mingus hated to be touched—a troublesome wart on her finger had miraculously vanished the next morning. Thisby found this quite amusing and never let the joke drop.

Thisby withdrew a large brown paper parcel from her backpack and tossed it to the ground several feet away. It landed with a wet thud. She checked an old, weathered notebook and muttered to herself.

“Drop off seven pounds of raw beef for the troll! Check! Oh! I almost forgot!”

Thisby reached into her backpack and withdrew a small burlap bag. From it, she pulled several branches of fragrant rosemary, which she tossed near the dripping brown paper parcel on the cave floor.

“Come on,” she said.

“Please be careful with me this time . . . I think the structural integrity of my jar may be weakening.”

“I could always take you out and have you sit on my shoulder. Like a parrot!” Thisby teased.

Mingus looked sicker than usual. “P-please, Thisby . . . don’t say that . . .”

“Geez! I’m only joking!”

She hooked Mingus’s lantern to its dedicated spot on her backpack and hoisted the monstrous bag onto her tiny shoulders. Thisby knew they had roughly four minutes before the smell of the raw meat would permeate the paper enough to rouse the troll from sleep. She also knew hungry trolls were most definitely not “morning people.” She’d found that one out the hard way. It was just another in a seemingly endless list of potentially deadly quirks she’d come to understand during her tenure as gamekeeper.

“Drop off seven pounds of raw beef for the troll! Check!”

She moved at a brisk trot farther down into the dungeon and blew into her hands to warm them. It was, in fact, unseasonably cold in the mountain today. Perhaps the ice wraiths had woken up from their hibernation early, she thought. Defrosting an ice wraith nest wasn’t exactly something she was looking forward to, but it needed to be done and nobody else was going to do it. Thisby pulled a small notebook from her pocket and scribbled some notes as she walked.

BIG GREEN = 7 MOO (+RM)

SLUSHIES = ZZZZZ?

It was going to be another busy day.

Castle Grimstone had existed for as long as the people of Three Fingers could remember, which isn’t really as impressive as it sounds. The villagers of Three Fingers rarely made it past the age of twenty-five, and the ones who did were too busy barely staying alive to remember things like when castles were built and all that other nonsense.

The castle stood atop a mountain, long ago corrupted by the vileness that dwelt within. Even moss would not dare grow on its craggy surface. The mountain was colloquially called the Black Mountain—its only name, actually, since nobody was brave enough to give it a formal one—and it was the biggest in all of Nth and quite possibly the entire world, though nobody but wizards had ever traveled far enough to see for themselves and nobody believed anything wizards had to say—and rightly so. But it was there, atop the mountain’s highest pinnacle, that Castle Grimstone had stood for as long as the blighted, dirt-farming yokels could remember.

Grimstone looked as if an angry four-year-old had smashed a toy castle apart and her poor, exasperated mother had hastily put it back together all wrong. There were all the telltale signs of a castle but there seemed to be no logic as to its construction. An excess of towers jutted out at irregular angles and none of the parapet walks made any sense. A few of them even seemed to be upside down. Nearly every exterior surface was covered in black iron spikes, which stuck out in every imaginable direction, and where you could see through, there were only black stones, perpetually wet and slick like they’d just been covered in fresh oil.

It was on her zero-th birthday that Thisby had first come to the castle. Her parents, a particularly dull and cruel pair of Three Fingers yokels, had traded her for a bag of mostly unspoiled turnips that morning, and by that afternoon the wandering salesman on the other end of the bargain was already lamenting the haste with which he’d accepted the deal. When he returned to insist upon a refund, he found that her parents had already used the turnips to make a paste to ward off bad spirits, which they’d promptly smeared all over their bodies. After giving it some serious thought, he decided that a trade back seemed unwise. Disheartened, he dumped the baby at the foot of the Black Mountain and vowed to be more thoughtful about his business decisions in the future.

It was nearly midnight when a blackdoor in the mountain opened and a shadowy figure peered out into the night, glancing at first right over the tiny newborn baby on the doorstep. When the towering, hairy figure went to step forward, something beneath its massive hoof made a strange gurgling sound. It looked down to find what seemed to be a miraculously as yet uncrushed human infant. The creature picked up the baby and thought for a moment. But he’d had a big lunch that day, so he took the baby inside for later.

He quickly scrawled a note, which he laid down atop the baby, nearly covering it completely, before shuffling back out into the night. The note read:

FOUND THIS BY THE STOOP.

PLEASE KEEP FOR LATER.

Fortunately for the baby, minotaur penmanship is notoriously sloppy, and several hours later when the goblin maintenance staff were cleaning up the kitchen, they lifted the sheet of paper off the squirming newborn baby and read it as thus:

FOUND, THISBY THESTOOP.

PLEASE KEEP FOREVER.

And so they did.

Chapter 2

Thisby finished her rounds in the dungeon before heading up to bed for a few precious hours of sleep. As she darted between the shadowy crawl spaces and hidden passages that only she was privy to, Mingus read off the list of chores that she’d dropped into his jar that morning. It was a sort of fail-safe they did every day to make sure she hadn’t missed anything. Mingus would read the name of the chores she’d completed one by one, and she’d respond with an audible “Check.”

She’d fed the troll, peeked in on the ice wraiths (which were thankfully still asleep), removed the bones from the ooze pit, watered the creeping death vines, baited the spike traps, reseeded the wereplant den, turned the hydra eggs, trimmed the griffin’s toenails, uncrusted the rock imps, and stabled the nightmares. As she half listened to Mingus reading the list, she’d already begun to think ahead to the new chores that were waiting for her tomorrow: dousing the rogue fire elementals, unsalting the meat for the slughemoth, polishing the ifrit lamps . . . and so on and so on, she thought, until she’d nearly made it all the way back to her room at the top of the mountain. But just before her hand could reach the iron ring on her door, Mingus read off one last item.

“Pick up the herbs from Shabul.”

“Che— Oh, no!”

Thisby raced back down the rickety ladder that led up to her room and darted across the wooden bridge that connected it to the castle cellar, her footsteps thumping against the makeshift boardwalk. She wasn’t technically allowed ins

ide the castle proper. The Master preferred to keep his dungeon separate from his castle, presumably because it was unsafe, but based on the kind of abhorrent creatures that freely roamed the castle halls with complete impunity, this seemed fairly unlikely. The far more likely scenario was that the Master simply preferred for his subjects to live in a constant state of fear and distrust. And just like every Master from every history of every world that has ever existed, he knew that the easiest way to achieve such a horrible state of fear and distrust was to separate his creatures into groups and arbitrarily tell one group that they were better or worse than the other groups. In the Black Mountain, there were a lot of groups.

As gamekeeper, Thisby was part of the staff and had more freedom than the enslaved monsters who lived in the dungeon. She had her own room as close to the top as one could hope to live while still residing in the mountain itself, and she was rarely beaten and usually had enough to eat. She didn’t have the clout of the staff that worked inside the castle of course, but as long as she finished her chores, she was able to come and go as she pleased. The catch, of course, being that her chores were never finished.

“Watch where you’re going!” hissed a voice from the darkness.

A mindworm the size of Thisby’s forearm, with twelve magnificent glittering eyes and a shiny, ruby-hued body, shrank back into its hiding hole as she ran past. Thisby ignored its angry hissing and tried to shake the image of her own gruesome death from her imagination as the worm chided her telepathically.

She removed a piece of wood from the cave wall, revealing a hole just big enough to fit her and her cumbersome backpack. Deciding not to wake the now-sleeping Mingus, who dangled from his usual hook—he’d returned to his normal grayish color—she entered the darkened tunnel without the aid of his light and relegated herself to bumping her elbows and cutting her knees against the crude, unforgiving rock walls.

The tunnel ran just below the edge of the castle and was so tight that she had to remove her backpack and slither flat on her belly for the last few feet. At the far end of the tunnel was an opening just wide enough for her head and shoulders to push through and peek out into the cool night air. The wind whipped her short, sweaty hair over her face so that it was hard to see the darkened pines that dotted the smaller mountains to the south.

Thisby Thestoop and the Wretched Scrattle

Thisby Thestoop and the Wretched Scrattle Thisby Thestoop and the Black Mountain

Thisby Thestoop and the Black Mountain